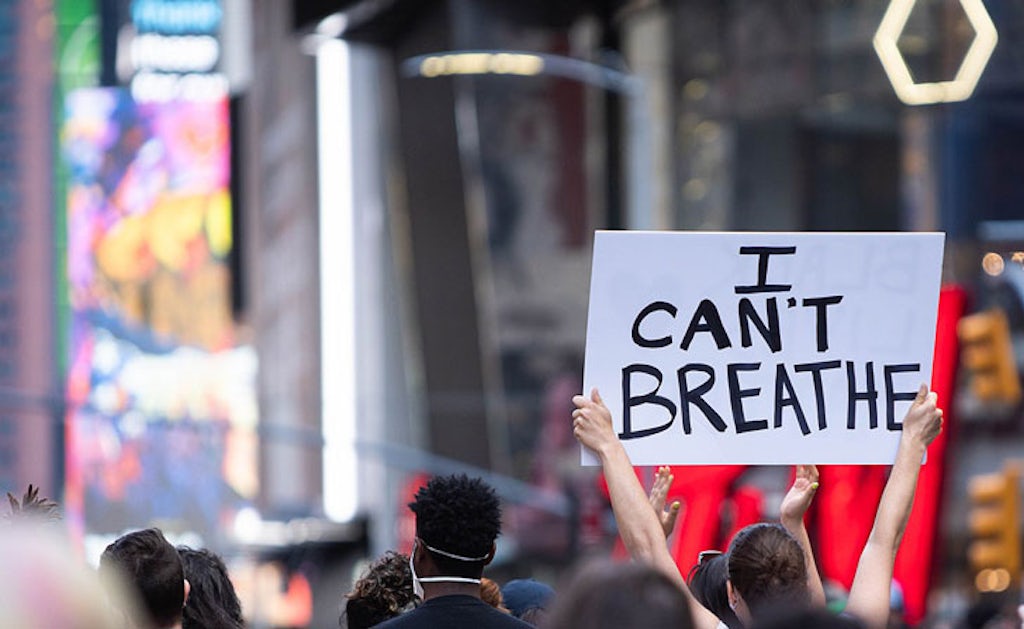

The killing of George Floyd, a black man who died after a police officer knelt on his neck for more than eight minutes, has sparked the biggest social unrest in the United States since the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. In cities and small towns across the country, Americans are demanding fundamental changes to the role of police in society. They are asking how criminal justice can be reshaped in a way that both protects civilians and ends the discriminatory and often violent treatment of disadvantaged communities at the hands of police.

For decades, the war on drugs has been one of the main vessels through which police interact with minorities, and it has exacted a devastating toll on non-white communities. Advocates of cannabis legalization have held it up as if not a panacea, then one of a number of tools that can change policing for the better, free up taxpayer resources, and funnel money and support to the very communities that have been the most affected by the prohibition.

But how has this promise played out so far? The legalization of medical and recreational cannabis has been overwhelmingly positive, but it turns out it’s not so cut and dry, which is exactly why the lessons of legalization — both its successes and failures in correcting those historic injustices — could prove valuable in this political moment.

A pretext for negative police interactions

The war on drugs has long served as a pretext for negative encounters between law enforcement and people in minority communities, said Sharone Mitchell, Jr., director of the criminal justice reform advocacy group, the Illinois Justice Project.

”If police were not radically enamored with the idea of enforcing the drug code then we could reduce engagement with the police in a negative way,” Mitchell said. “So I think it’s the biggest doorway to these encounters that end so tragically.”

The Illinois Justice Project is one of a number of organizations that have supported the state of Illinois in the development of the Restore, Reinvest, and Renew Program (R3). The program aims to invest 25% of net adult-use cannabis sales revenue into communities “most impacted by mass incarceration and the war on drugs.”

Signed into law by Governor J.B. Pritzker last year, the program will use tax revenue “to fund strategies that focus on violence prevention, re-entry and health services to areas across the state that are objectively found to be acutely suffering from the horrors of violence, bolstered by concentrated disinvestment.”

In May, the state of Illinois announced that as part of the program it will invest $31.5 million in cannabis tax revenue as “restorative justice grants.”

Investing in solutions before any crime takes place

According to Mitchell Jr., programs like R3 flip the typical approach of addressing social ills after the fact, through enforcement.

“Too often when trying to approach issues of crime and other things that are going on poorly in the community, we throw all of our dollars and all our attention on punishment, and come into things after the situation has already gone down,” he explained. “We’re calling on policy leaders to invest in solutions before they take place.”

As it stands today, the war on drugs has instead worsened violence and social ills, according to Mitchell Jr., through “the intentional disinvestment in communities and increased criminal records.”

People are coming back from prison without the ability to get an education, housing, jobs, and health care, he said, which excludes them out of the legitimate economy and contributes to crime and violence.

Almost four times more likely to be arrested for marijuana

“The price paid by those arrested and convicted of marijuana possession can be significant and linger for years, if not a lifetime,” stated a 2013 report by the American Civil Liberties Union. “Arrests and convictions for possessing marijuana can negatively impact public housing and student financial aid eligibility, employment opportunities, child custody determinations, and immigration status.”

Those consequences are not equally borne across society.

A black person is 3.73 times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession than a white person, and this disparity exists in towns and cities large and small, urban and rural communities, and in wealthy and poor areas, according to the ACLU.

But while drug laws do give police a pretext to stop and search people, does legalization actually solve this problem?

Not quite, according to Adam Vine, the co-founder of “Cage-Free Cannabis,” which works to “support the repair of harms of the War on Drugs.”

“We can’t just take it for granted that legalization leads to racial justice — it doesn’t,” Vine said, adding that in some jurisdictions that have legalized there has been a spike in arrests of minorities for public consumption.

Legalization boosted funding for police departments

This to some extent reflects the findings of a 2019 study published by the University of Pennsylvania which found that “in all ‘legalized’ states, the disproportionate impact of drug arrests, including for marijuana, remains stubbornly high, contrary to what legalization proponents suggest. The charge that marijuana legalization will eliminate racial bias in the justice system is unfounded. The opposite has been proven.”

The researchers cite how after legalization went into effects in Washington D.C., arrests for redistribution and public consumption of marijuana nearly quadrupled, and 84.9% of those arrested were African Americans.

“An objective study of the data shows the high promises of social justice have failed to come to fruition. In states that have ‘legalized’ recreational marijuana under the premise of reducing social injustice, arrest rates for certain marijuana-related offenses have increased, particularly for young minority groups,” the study stated.

There is also the fact that legalization has served to boost funding for police departments in states where it has gone into effect.

Removing the ‘justification’ for violence

Nonetheless, Vine says that decriminalization of marijuana could prevent hundreds of thousands of arrests each year — which disproportionately affect minorities.

“Whether in the moment or after the fact they’ll often look at cannabis as a way to justify the violence. They’ll use it as probable cause for the stop or as a way to sort of defame the character of the person who’s been killed after the fact,” Vine said.

He cited as examples the fatal police killings of Philando Castile in Minnesota in 2017, and Bonham Jean in Dallas in 2018. In the case of Castile, a police officer said that he smelled marijuana and that caused him to fear for his life. After Bonham Jean was killed, news that police found marijuana in his apartment was leaked to the press, in an apparent attempt to smear his image posthumously.

Also, he added, fewer cannabis arrests means fewer people dealing with fines, fees, incarceration, and the social stigma that comes with entering the criminal justice system. This can cause difficulties in finding employment or housing, access to public benefits, and in some states, the right to vote.

Legalization hasn’t solved economic inequalities

Another aspect of the legalization debate that people are not taking into consideration enough is who benefits from the legal cannabis industry. According to a 2017 survey, only 17% of cannabis executives were minorities, and a 2016 analysis by Buzzfeed based on interviews with 150 industry insiders estimated that only 1% of the more-than 3,000 marijuana storefronts in the United States had black owners.

According to Richard Cowan, the former national head of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) the problem is largely due to stringent regulations about who can enter the cannabis business. Authorities, he said, should “just get out of the way and let people open [dispensaries] in their communities.”

To Cage-Free Cannabis co-founder Andrew Epstein, the racial disparities in the Cannabis industry highlight the need for a more measured and gradual approach to legalization.

One of the big mistakes of recent legalization pushes, he explained, is that authorities moved too quickly, thereby not operating in an environment to have equitable legalization. “Basically, what we had was legalization and everybody rushing in and the ones that rushed in are the ones who had the means.”

The entry barrier is usually a very large sum of money up front, in cash, and in most states people with prior drug convictions — who are disproportionately minorities — are not allowed to own cannabis businesses.

“For the 100 or so years of the war on drugs that’s been away for law enforcement to essentially loot communities of color, to take their liberty, to take their money, and at times to take their lives,” Vine said, adding “so if that’s the point that we’re starting from and you then commercialize this business and if you’re saying people need a million dollars in assets to enter the industry then there’s a terrible disparity that you’ve just introduced.”

The issue of racial equality in cannabis may also be linked to the fact that the cause of legalization has mainly been led by white activists from white communities, or as Cowan recently wrote of NORML, “I joked that it was the whitest organization that I had ever belonged to that didn’t have a tennis court.”

Regardless, while cannabis tax revenue and programs like R3 have the potential to help revitalize communities and legalization can mean fewer people — of all races — entering the criminal justice system, legalization has yet to end the war on drugs.

“I think there is this kind of tone that we are moving away from the war on drugs because we’re allowing people to profit on certain types of sales but man, the war on drugs is still alive and well and poppin,” Mitchell Jr. says.

Sign up for bi-weekly updates, packed full of cannabis education, recipes, and tips. Your inbox will love it.

Shop

Shop Support

Support