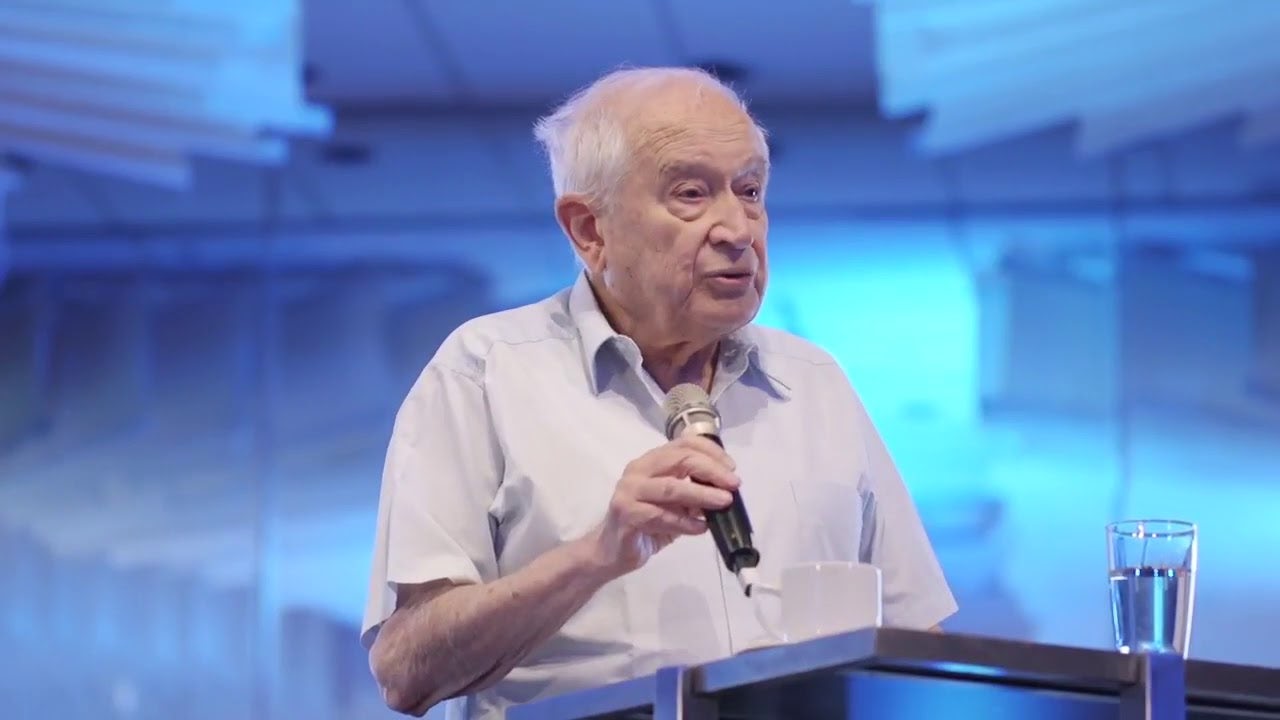

Many people have heard of Raphael Mechoulam, the Israeli scientist and “godfather of cannabis” who isolated THC in the 1960s. However, Israel’s connection to marijuana has a lot more to it than one man or any single discovery.

Fun fact: Cannabis was made illegal in Israel before the country even became an independent state in 1948. It was included in the 1936 “Dangerous drugs ordinance,” written by the British High (no pun intended) Commissioner of Palestine when the country was still under the British rule. In 1961, Israel joined as a signatory of the UN’s 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, a document that laid much of the foundations of international cannabis prohibition as we know it. A few years later, in 1973, the Israeli parliament amended the 1936 act, but notably kept cannabis research legal. In contrast, in the US, cannabis research was — and still is — extremely restricted by federal drug prohibitions.

Groundbreaking Cannabis Research

In the early 1960s Mechoulam, a young scientist from the Weizmann Institute, set about researching cannabis. According to Mechoulam, cannabis research back then was almost totally neglected for two main reasons. First, cannabis was an illegal substance, hence not very accessible to scientists and research laboratories. “Even if obtained legally, research with it was a laboratory nightmare,” he told Addiction magazine.

“I went to the administrative director of the Weizmann Institute and simply asked him whether he knew somebody at police headquarters… he called the head of the investigative branch at police headquarters with whom he had been together in the army. I heard the police officer asking ‘Is he (meaning me) reliable?’ On receiving a positive answer, he asked me to come over to Tel Aviv and thus I obtained five kilograms of superb, smuggled Lebanese hashish,” Mechoulam said.

The second reason was that pure, isolated forms of the active chemical compounds in the cannabis plant were not yet available for research. Other major plant-derived illicit drugs, such as opium and coca, were already isolated in the 19th century, i.e. morphine and cocaine. The availability of these pure compounds made biochemical, pharmacological, and clinical research possible. Mechoulam had his work cut out for him.

The Next Generation of Researchers

He got together with some colleagues and formed a cannabis research team. First Yuval Shvo joined, and together they re-isolated and established the structure of cannabidiol, also known as CBD. CBD was first isolated by Roger Adams in the 1940s but its structure was only partially known, which was Mechoulam’s team’s first breakthrough. Shortly after, two others — Yehiel Gaoni, who had just finished his PhD in organic chemistry from the Sorbonne, and Haviv Edery, who immigrated from Argentina a few years earlier — joined the team. Their goal was to solve the first cannabis enigma — by identifying the active constituents of cannabis. First, they identified the structure of THC, continuing with the discovery of several other “minor” cannabinoids.

In the late 1980s, much of the next generation of cannabis researchers performed some of their most important work in Israel, many of them alongside Mechoulam. The two key figures were Bill Devane, who was a part of the US research team that discovered the first cannabis receptor, and Lumír Hanuš, a Czech researcher who had already been involved in cannabinoid research in his home country. Together with Mechoulam, the two discovered Anandamide in 1992, the first endogenous cannabinoid (aka endocannabinoid). Their work, together and apart, led to the discovery of the endocannabinoid system, considered another scientific and medical breakthrough. Both Devane and Hanuš have been heavily involved in cannabis research ever since.

Israeli cannabis research has also influenced important work taking place abroad. For instance, cannabis research superstar Dr. Ethan Russo, who is responsible for the popularity of concepts such as the Entourage Effect and Clinical Endocannabinoid Deficiency, started his cannabis research in the late 1990s and considers Mechoulam to be one of his mentors.

Ripe Conditions for Clinical Studies

The Israeli Ministry of Health started issuing medical cannabis permits for individual patients in the late 1990s. The common indications for cannabis treatment were HIV/AIDS and cancer, but in reality only a handful of patients applied for permits and even fewer were granted.

Most eligible patients were very ill and incapable of navigating the logistical and bureaucratic process of getting a permit and cultivating their own cannabis. If patients did manage to obtain a plant or seeds, most people lacked the knowledge and equipment to grow their own cannabis.

That all changed when a few permit holders started a cannabis cultivation collective, Tikun Olam (Hebrew for “repairing the world”). This group of volunteers got a permit to grow 100 cannabis plants for other patients, and also introduced the medical use of cannabis to seniors, traveling from one retirement home to another, promoting the use of cannabis for therapeutic purposes. Eventually the number of permit holders was such that Tikun Olam couldn’t keep operating as an NGO and became a private company in 2010. Seven other cannabis producers began operations in the country that same year.

The medical use of cannabis in Israel has continued to grow year after year, with 2,000 patients treated with in 2009, 22,000 in 2015, and approximately 50,000 in 2019. This growth created the conditions for more, and different types of cannabis research as well. Prior to Tikun Olam’s activity, research in Israel was mainly preclinical but with such access to a large pool of medical cannabis patients, clinical studies looking at real patients started to emerge, especially for conditions such as epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

At the same time, a new generation of cannabis researchers came into its own. Two good examples are Dedi Meiri from the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, and Yossi Tam from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Meiri runs the Laboratory of Cancer Biology and Cannabinoids Research investigating subjects such as the therapeutic potential of cannabinoids and he principally focuses on different types of cancer, epilepsy, and diabetes. Yossi Tam is the Head of the Multidisciplinary Center for Cannabinoid Research at the Hebrew University, which consists of dozens of researchers from a variety of fields looking into subjects such as inflammation, pain, the immune system, metabolism, and cancer.

Even though Israel’s medical cannabis program started in the 1990s, it still has a lot of limitations. Patients often complain about access, difficulty obtaining a prescription, and high costs that aren’t covered by health insurance.

Sign up for bi-weekly updates, packed full of cannabis education, recipes, and tips. Your inbox will love it.

Shop

Shop Support

Support