Off the coast of British Mandatory Palestine, two bandits hide in a tiny sailboat as it bobs on the waves. They await their mark and as a southbound smuggling ship crosses their path, skipper Aryeh Bayevski and his friend Isaac intercept the boat, rush on board brandishing knives and hatchets, and rob the smugglers of their hashish shipment.

The smugglers sail back to Lebanon or Syria to try their luck a different day, while the two Jewish would-be pirates head for shore to spend the booty on “wild campfire drinking.”

This story of ad-hoc piracy off the coast of modern day Israel is but one of many anecdotes in “Intoxicating Zion: A Social History of Hashish in Mandatory Palestine and Israel,” published in October by Stanford University Press. Billed as “the first book to tell the story of hashish in Mandatory Palestine and Israel,” it depicts how following World War I, Palestine became the most important transit point for hashish in the Middle East, leaving British and French colonial authorities — and later Israeli law enforcement — utterly at a loss to stop the flow of hashish.

It also paints a compelling picture of the ways in which the same anti-cannabis propaganda of the “Reefer Madness” era found an audience in Israel, where fear-mongering about hashish adopted a very similar, racially charged, panicked tone to the one that took hold stateside.

The book was released in early October, though Author Haggai Ram said he has yet to receive his copy of the book — as it, perhaps fittingly, disappeared after it entered customs in Israel.

How Israel became a smuggling hub of the Levant

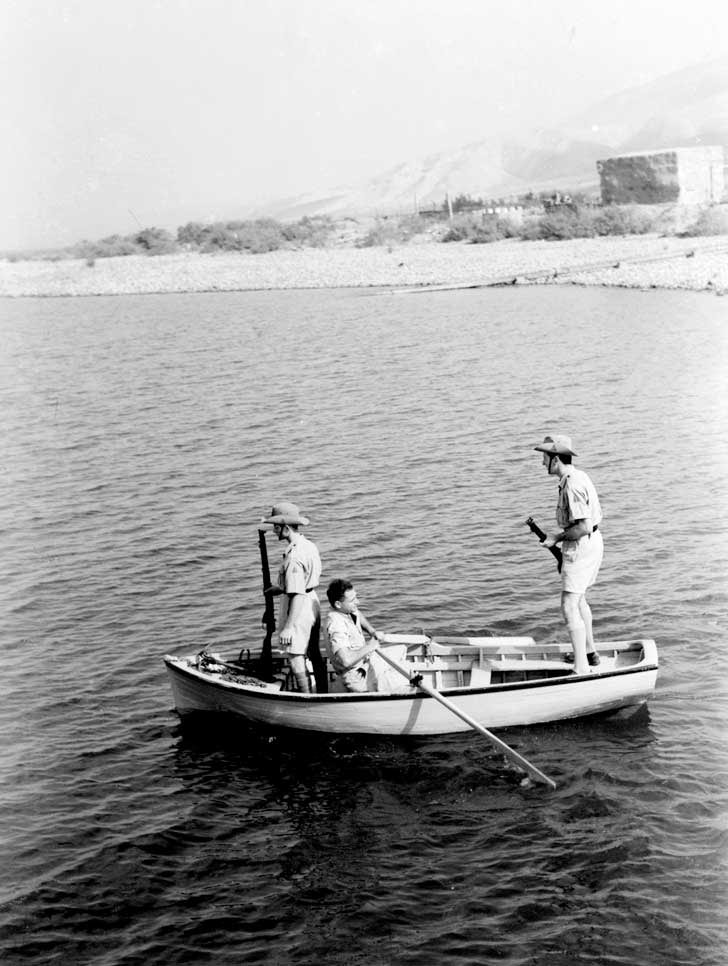

During the years covered in the book — from the 1920s during the British Mandate in Palestine and up to Israel’s victory in the Six Day War in 1967 — the country was the main trafficking route for hash traveling from Lebanon and Syria to Egypt, then the region’s largest consumer market for hashish. The book describes how smuggling hashish to Egypt was a massive business for traffickers sailing in boats from Greece — then the main source country for Egypt-bound hashish — which would be spirited across the Mediterranean in boats from the small islands in the Greek archipelago where cannabis was grown at the time.

The book describes how anti-cannabis measures began in earnest in Greece in the 1920s leading to the country’s eventual prohibition on cannabis cultivation in 1932. From that point on, the Levant hashish trade from grow operations in Lebanon and Syria south across Palestine to Egypt reigned supreme.

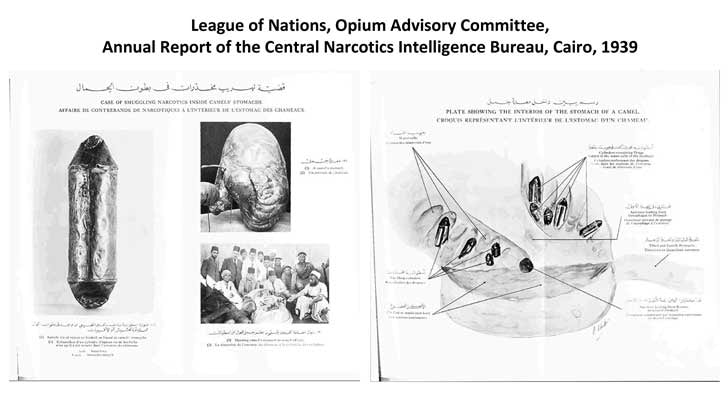

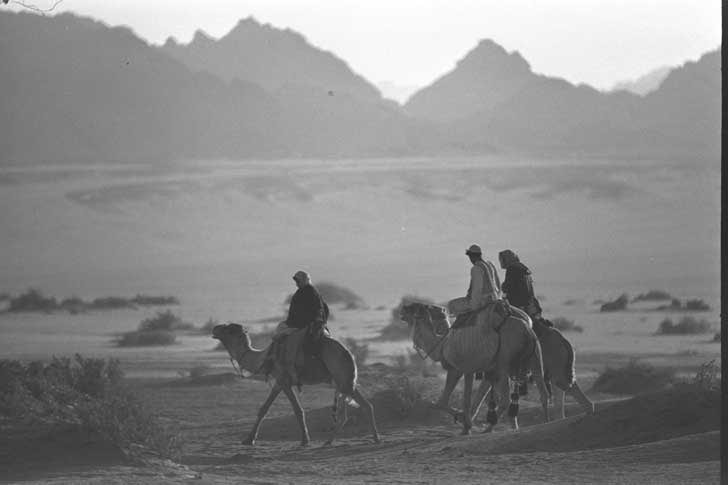

Ram paints a picture of law enforcement authorities who were totally outnumbered and no match for the smuggling schemes by sea and by land, especially in the south of the country, where Bedouin smugglers made an especially challenging quarry. They knew the desert better than anyone, but they also had especially sophisticated and cruel methods of hiding their contraband — both on and later inside their camels.

“During the interwar period these very “sons of the desert” successfully deceived British colonial officials in Palestine (and Egypt) with an extremely sophisticated and unpleasant ruse for smuggling hashish: concealing packages of the drug inside the stomachs of camels, and — after making it safely across the border into Egypt — cutting the unfortunate beasts open to retrieve the treasure. In due course, the authorities came up with an equally imaginative method for dealing with this subterfuge. Because the concealed hashish was forced down the beasts’ throats in tin containers, X-ray machines and mine detectors were deployed to the Palestinian-Egyptian border to inspect the insides of camels,” Ram writes.

But smugglers are nothing if not resourceful, and in time they would soon start using plastic and leather containers for the intra-camel containers, side-stepping the X-ray machines.

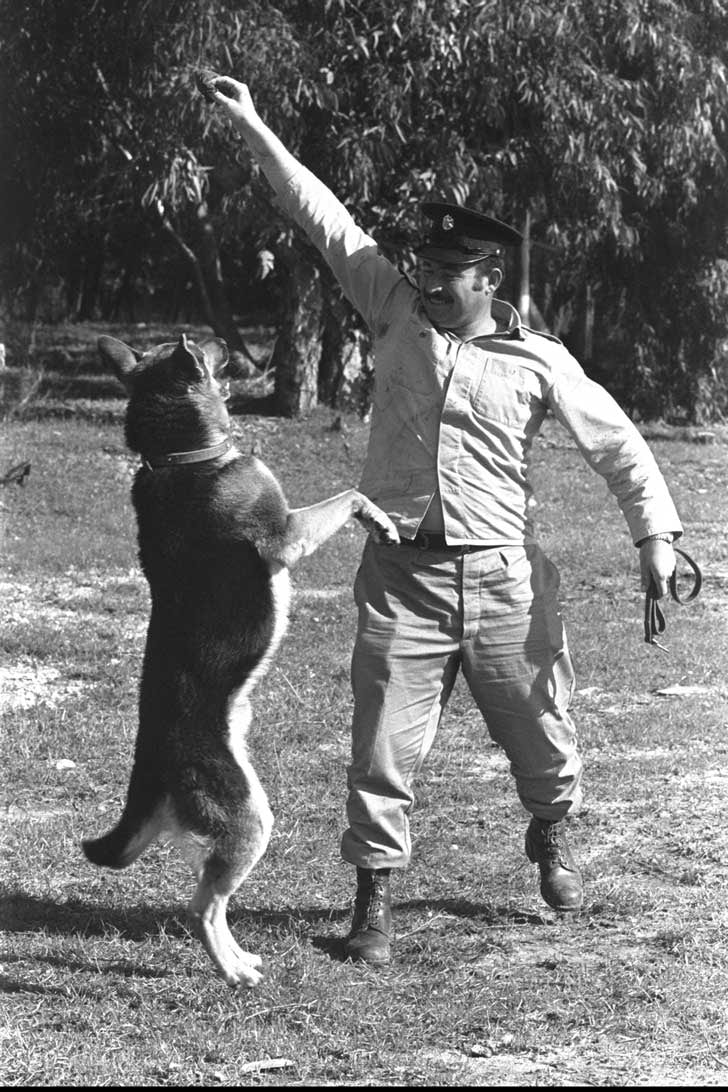

The book also details how in 1953, Israeli authorities deployed a canine unit to fight hashish smuggling, and citing an Israeli newspaper article from the time, asserts that it made Israel “apparently the first country ever to make use of sniffing dogs to discover drugs.” (The canine cop was given the rather predictable name “Lassie.”)

A censored history: The military angle

Being that the book covers Israel, it’s understandable that the Israeli military plays a not negligible role in the story. Ram addresses the assertions made by the Arab League and others that claimed that Israel used its army to smuggle hash from Lebanon to Egypt through Israel so as to weaken and debilitate the Egyptian army. Ram said the story has not been confirmed, but that Israeli courts and governments have put their weight behind silencing any material that could be related to the “alleged” smuggling.

Ram also highlights how hashish featured prominently in one of the major arguments used in Israel to explain the swift victory over the Egyptian army in the Six Day War in 1967 — that is, “the entire Egyptian army was stupefied on hash and unable to fight,” as Ram describes the theory.

“Israel and the Israeli army waged a war against hashish inside the Israeli army, so that Israel will not become like a so-called ‘Second Egypt’,” Ram explained, which in hindsight may seem rather ironic considering that Israel has one of the highest rates of recreational cannabis use on Earth (a 2017 survey by Israel’s Anti-Drug Authority found that 27% of all adults aged 18-65 reported using cannabis in the previous year.)

There’s also the matter — detailed in the book — of how Israel’s military occupation of Lebanon from 1982-2000 “further normalized hash use in Israel,” in no small part because “Israeli military servicemen and Israeli civilians with access to occupied Lebanon were crucial intermediaries in this trade — with many of the lower ranking soldiers concealing hashish in rifle magazines and inside weapons, and military officers concluding lucrative hashish deals with major Lebanese drug lords.”

What hash can teach us about ourselves

Ram said it took him a decade to write the book, mainly because of a shortage of sources on the subject. And since he was covering an industry and a culture that lives in the shadows — and since we usually only hear about smugglers after they get caught — it was a difficult process. In the end, he relied largely on press reports, memoirs, books, and government and police reports from Israel, Europe, and elsewhere in the region.

When asked why as a longtime expert on Iran he took up this subject Ram said “since the cultural turn in the 1970s, 80s, 90s, there is a growing interest in precisely such subjects which might be esoteric but they allow you to gain insight into very interesting political and cultural and social processes that occur in each and every society.”

And what did this mean for Israeli society? As Ram put it, “hashish enabled Israel to distinguish itself from the Arabs and also to cut down or marginalize Mizrahim (Jews of Middle Eastern and North African descent), so there is growing awareness among social historians that topics that may seem esoteric may actually give you a better understanding of the ways that societies see themselves, organizes themselves, and how they view the “other.”

The way hashish was viewed in Israel is part of a wider regional phenomenon that stretches back for centuries, Ram stated.

Reefer Madness, Middle East style: Using hash to marginalize minorities

“Hashish since the Middle Ages has been identified with stigmatized groups and minorities, whether ethnic or linguistic or religious. Hashish is the drug of the lower classes par excellence, everywhere it has, historically. And it is perhaps the most important drug that has gone through an Orientalization process so it was kind of a pretext to exclude these classes and minorities and counterculture groups to distance them and discredit them as not being part of the national collective.”

For an American audience, what may be the most fascinating aspect of the book is the way in which racist portrayals of the “underclass” went hand in hand with the way that Israeli authorities and the “white” Israeli elite described hashish — and the people who used and trafficked it. Namely, hashish was seen as an Eastern, Arab vice, and those Jews who would deign to consume it were assumed to be Mizrahim, Jews who immigrated from Arab and Middle Eastern countries, who were at the bottom of the social hierarchy among the Jews of Israel. To consume hashish, as the popular portrayals went, was to adopt a vice associated with the lower classes and the Arabs, one that would corrupt good Israeli (Jewish) youth, and endanger the entire Zionist enterprise.

“After 1948, as the migrant Jews of Middle Eastern and North African descent (or Mizrahim) were pushed to the margins of society, and themselves became associated with hashish smoking, the state authorities feared that the habit would lead to the Levantinization of Israeli society and viewed it as an indication of pre-modern, primitive ways of life,” Ram writes.

The main reason for “nearly universal Jewish abstention” from hashish in Israel, according to Ram, was “the fear of accommodating an ‘alien’ Oriental artifact — hashish — in much the same way that the white middle classes in the United States of the time were wary of marijuana, because of its association with “alien” Mexicans and Blacks.”

But perhaps similar to the ways in which in the US jazz clubs and marijuana were portrayed as a slippery slope that would lead to “race mixing” and moral decay, in Israel “hashish dens, coffeehouses, and brothels, where Arabs and Jews could commingle and assimilate while sharing a hashish-filled cigarette or a hookah, were construed as a national-political threat.”

When white bohemians started getting high

And just as perceptions of cannabis began to slowly change in the US when it became popular with hippies, artists, and musicians around the time of the Summer of Love, a similar phenomenon happened in Israel, after Tel Aviv’s white Jewish bohemia began to fall in love with weed.

“At about the very same time that the Mizrahim were being condemned for hashish smoking, a limited but growing number of Jewish Israeli “bohemians” — literary figures, musicians, singers, artists, and other personalities in the entertainment and intellectual world — were also beginning to experiment with hashish as part of a cultural counter-movement,” Ram writes.

He adds, “the antagonistic and paternalistic (not to say racist) reaction to Mizrahim who smoked hashish, as examined above, may be contrasted to the way the same habit was perceived where the Israeli bohemia was concerned. While hashish smoking by Mizrahim and Arabs was viewed as a cultural or even racial deficiency, a symbol of their backwardness, deviancy and innate criminality, the same behavior by members of the Israeli bohemia was excused, and even described in positive terms (although it too was sometimes condemned as a corrupting practice that might spread among innocent Israeli youngsters).”

Military expansion leads to new smuggling routes

The book ends in 1967, after Israel’s victory in the Six Day War, during which Israel occupied the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Golan Heights, and Sinai Peninsula, creating an even more advantageous situation for smugglers moving drugs south to Egypt. The book doesn’t describe the current situation in Israel, where legalization is expected to go into effect in the coming years, and where there is a large medical cannabis industry and a recreational industry that is chomping at the bit to get off the ground.

Ram did tell The Cannigma though, that just like how the same “Reefer Madness” propaganda that took hold in the US spread in Israel, another American reality can be seen in Israel as well: the way that the same people — in the US, mainly Black and hispanic — who were the main victims of cannabis prohibition are not those who are benefiting the most from the legal cannabis industry. In Israel, widespread hashish usage was spurred by traffickers, and given a life of its own in the shadows by the Arab and Mizrachi lower classes — who are not in the driver’s seat now that cannabis is stepping out into the light.

Sign up for bi-weekly updates, packed full of cannabis education, recipes, and tips. Your inbox will love it.

Shop

Shop Support

Support